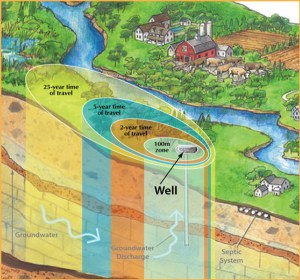

From where I’m looking there seems to be a love-hate relationship with salt. Sure it is bad for me, groundwater – your drinking water. But when it’s time to deal with snow and ice, there isn’t anything else that works quite like salt.

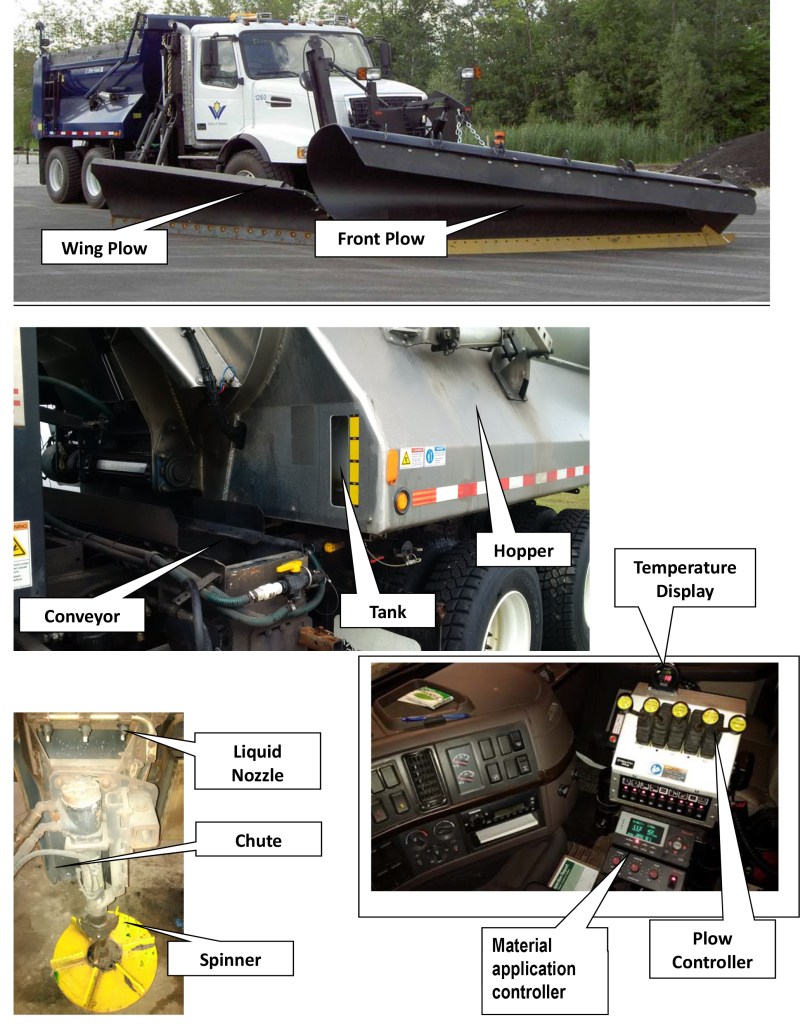

Have you ever thought about how much of your community is paved? There are the roads, community trails, sidewalks, driveways and parking lots. During the winter, all these areas need to be kept clear of snow and ice for both accessibility and safety.

When it comes to the environmental impacts of salt, the tendency is to point the finger at other people and groups. They are the reason so much salt is spread.

What if I told you everyone, to some degree, contributes to the problem but can also be part of the solution. How can that be? You might be thinking “I don’t use much, if any salt” or “I only use such a small amount compared to others”.

That might be so but let’s think about why salt is used. Sure it makes removing snow and ice that much easier by lowering the freezing point when water in its liquid form changes to ice. That’s more of a technical answer but the reasons go much deeper making it a complex problem to solve.

Here are a few of those reasons why so much salt is spread.

- Liability. The fear of being sued is one of the biggest reasons businesses spread so much salt. Too much is used and it’s spread even when it’s not needed or when it’s too cold for the salt to be effective.

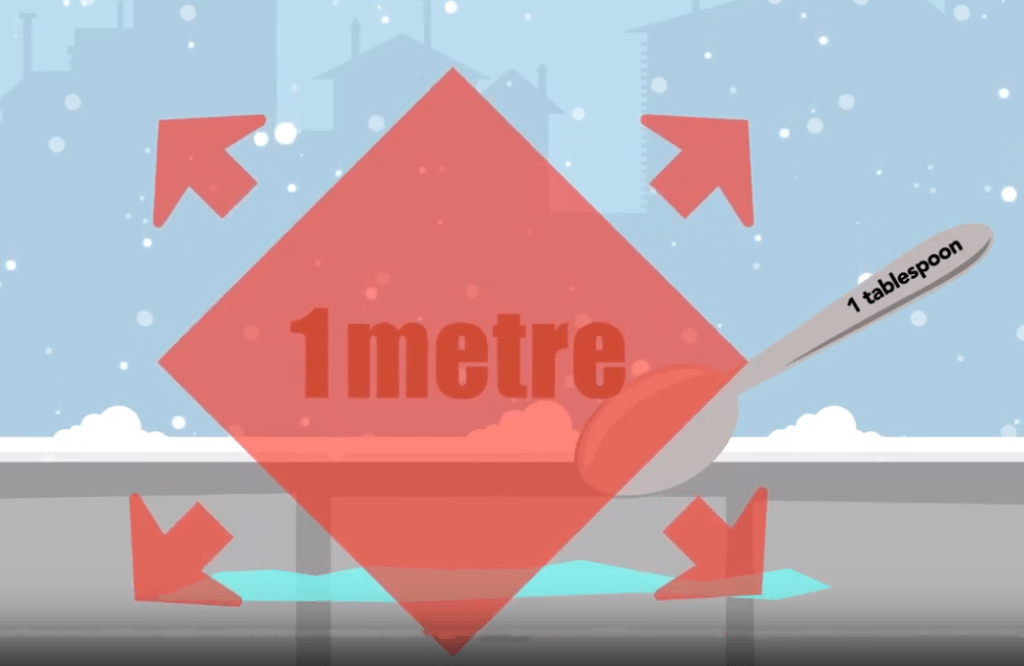

- Salt means safety. When you go for a walk or drive and see salt, it can make you feel safe. You know the property owner is doing their part to clear the snow and ice. But what if you don’t see salt on the ground. Does that mean it isn’t safe? Should you demand the property spread more salt? Maybe there isn’t any ice and salt isn’t necessary. Maybe salt isn’t the right tool for the current weather conditions. Or maybe the right amount of salt has already been put down and has turned into a liquid brine that – even though you can’t see it – is still hard at work. Whatever the reason, salt is not always the right or only tool for dealing with snow and ice. And not seeing salt on the ground doesn’t necessarily mean it is less safe.

3. Expectations. It’s winter. You are going to have to deal with snow and ice at some point. Yet there is an expectation to be able to travel the same as if it was summer. For this to be a reality can mean more salt spread to speed up the melting process. Is there a way to balance expectations for clear passage while still protecting me – your drinking water – from the damaging impacts of salt?

4. Changing weather. In Southern Ontario, winter can mean snow, freezing rain, rain, warm temperatures, or really cold temperatures. You get where I’m going with this. As weather patterns change, meeting expectations to keep areas clear of snow and ice can be a challenge and might include the spreading of more salt to meet expectations of clear pavement all of the time.

5. Personal safety. Wearing winter boots and switching to winter tires can seem like an inconvenience and an unnecessary expense. But living where there’s snow and ice should include taking these preventative steps to protect yourself. This also means giving yourself extra time to get to your destination and driving, biking or walking for the current weather conditions.

Not everyone uses salt but everyone at some point uses the surfaces that are salted. Changing actions and expectations over time might help support the responsible use of salt required to better protect the environment including me, groundwater – your drinking water, because – well – I think I’m worth protecting.

Cheers, Groundwater

Related posts: