Maps are great tools. They can help you find where you are, provide information on nearby landmarks and help guide you to your final destination. Remember the good ole days of paper maps? Now-a-days I’m guessing many of you use a GPS or an APP on your phone to help you get around.

For me – groundwater, I don’t really need a map. Partly because it would be really hard to read down here in the aquifer but mostly because I honestly don’t care where I am or where I end up. For me, there are no borders or boundaries thanks in part to the water cycle.

However, my friends at the Region of Waterloo seem to think otherwise. They like to track my every movement – where I soak into the ground, how long I’m underground and the different paths I take to reach the 120+ municipal supply wells in Waterloo Region.

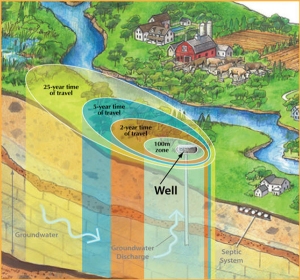

Each municipal supply well is in a Wellhead Protection Area made up of four zones: 100-metres, 2 years, 5 years and 25 years. The 100-metre zone is the closest to the supply well, with the remaining zones marking the time it takes for me to reach the well.

Image credit: Conservation Ontario

Understanding the geology of the land

With the help of computer modeling, hydrogeologists can track my movement and use this information to create Wellhead Protection Area maps.

To understand how I move underground you first need to know what materials I’m moving through. Aquifers, where you can find me, are made of different layers of materials such as sand, gravel, clay and bedrock. No two aquifers are the same. The layers in one aquifer can be very different from another. And in fact, the types of materials and how they are layered can change in a single aquifer.

As I slowly move through the spaces between these materials I travel at different rates of speed. Sand is like a sponge, slowing me down as well as acting as a natural filter. Rocks and gravel with larger spaces or cracks provide me with more room so I can travel at a quicker pace compared to sand. Clay is like a big ole stop sign for me. Its hard-packed and dense material acts as a barrier forcing me to change my route.

Why Wellhead Protection Area maps are important

One reason Wellhead Protection Areas are important is they help bring attention to me. When you look around it’s easy to see the lakes and streams. But I hide underground so I don’t always get the attention I deserve. You know the saying – out of sight – out of mind.

The maps help make groundwater real and hopefully more valued. They provide important information on my whereabouts and the journey I take to each municipal supply well.

And finally, the Wellhead Protection Area maps are an important groundwater protection tool supporting actions using the Source Water Protection Plan to reduce risks from pollution to groundwater.

And as the official drinking water for Waterloo Region, I’d like to think I’m worth protecting.

Cheers, Groundwater

Wellhead Protection Area maps show how groundwater moves to each of the @RegionWaterloo 120 supply wells. An important Source Protection tool for reducing risks of pollutants to groundwater. #iamgroundwaterblog

Tweet

Related posts: